Today we kick off a series of posts about writing chapter books. In his article “How Reading Volume Affects both Reading Fluency and Reading Achievement,” Richard L. Allington states, “The evidence we have is consistent and clear: Children who elect to read voluntarily develop all sorts of reading proficiencies, not just the ability to read fluently” (14). Chapter books are often those first books that children elect to read voluntarily. Built for emerging through proficient readers, chapter books bridge the gap between learning to read and reading for pleasure.

I remember well some of the first chapter books that introduced me to unforgettable characters such Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby and Ralph S. Mouse. I adored Judy Blume’s Fudge series (Dutton). My own children enjoyed Mary Pope Osborne’s Magic Tree House series (Random House) and the American Girl books (Pleasant Company). Reading chapter books as a young child is empowering and exciting. Sometimes it’s intimating and a struggle.

Chapter books differ from middle grade novels in that they usually include illustrations, larger type, shorter chapters, and fewer subplots. Word count can range anywhere from 4,000 words to 20,000 words. We’ll hear from four authors this week who are writing chapter books for young readers today about how they approach their craft.

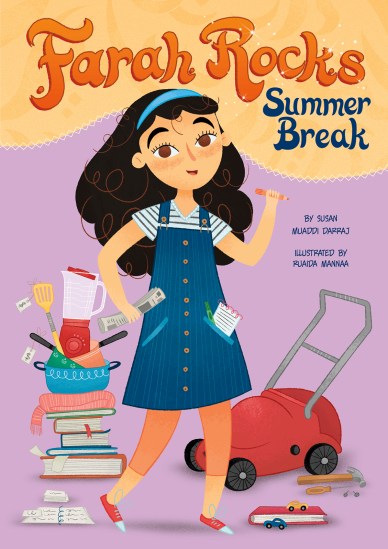

Today we welcome Susan Muaddi Darraj who won the Arab American Book Award for her Farah Rocks series illustrated by Ruaida Mannaa (Capstone), the first chapter book series to feature a Palestinian American protagonist. Welcome, Susan!

What appeals to you about writing chapter books?

Chapter books are an important bridge to reading fluency – they are the first books kids read with minimal illustrations. They are longer texts divided into actual chapters, and so they feel like a “big kid’s” book. This is a critical time in a young reader’s life, because they are independently reading. I get excited by the idea of sharing that moment with them.

Some of my favorite books were chapter books when I was younger: Ann M. Martin’s The Baby-Sitter’s Club series (Scholastic) and Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking books (Rabén and Sjögren) – I loved Pippi!

Character is crucial to all storytelling. How do you approach creating characters for chapter books, and how does this process compare to creating characters for other forms?

The process is the same for writing middle-grade or YA novels, or even writing novels for adults: Your character must struggle a bit. Sometimes, they may even disappoint you with their choices or behavior.

Usually, we are invested so deeply in forming our characters that we want to protect them in a sense. However, your character should roam freely in your imagination, which means allowing them to make errors or encounter problems.

Also, their problems in life have to be real. I never “talk down” to my reader. My character, Farah, comes from a family that is financially struggling, and she knows it. I try to remember that many of the kids reading my books are also struggling day-to-day. Some of them may be food insecure, some of them may have home lives that are unsettling, or they might struggle in school with academics or even with other kids.

They don’t want to read about a protagonist whose life trips along perfectly. They need to see how other kids handle difficulties, so as a writer, you have to create a character and then place them into a difficult situation (or more than one!).

How did your lived experience and perspective bring to your story?

I grew up in the United States as the daughter of Palestinian immigrants, and I remember feeling quite misunderstood and misrepresented by my non-Arab social circle. Why did my friends, for example, have preconceived notions (and negative ones, to be specific!) about my father, my culture, etc.? I felt like every conversation was an educational experience, in which I was correcting stereotypes about my background.

In other words, every time my ethnicity was was brought up, it meant I had work to do. It was exhausting.

When you’re a person of color, the questions people ask you can be quite unbelievable! When I imagined the Farah Rocks series, I wanted to create a utopia – what if a Palestinian American girl lived in a society that was rich in diversity and in which she moved seamlessly between her home, where she spoke Arabic, and her school, where she spoke English? And what if that did not cause a problem whatsoever?! What if she took hummus or za’atar to school for lunch and didn’t get teased? It was a great joy to imagine that, and so I named her Farah because the name actually means “joy” in Arabic.

What advice do you have for others interested in writing chapter books?

Start with a dynamic character who is around the age of your reader – usually upper-elementary school or 7-10 years old. Kids like to read about protagonists who are older than they are, so consider that. If your ideal reader is a fourth-grader, make your character a fifth-grader.

Remember that your audience is just becoming more fluent in their reading skills. A book like yours, which will be the first text-heavy book they read independently, can be daunting. Help them move through your book and maintain their enthusiasm by writing shorter chapters than you normally might. Include a lot of dialogue to help them get to know the characters better, and break up long paragraphs of text into shorter “chunks.”

They do not have the benefit of illustration to imagine the character – they are depending on your words to form a mental picture, so again, help them by “defining” each of your characters. Assign each character, especially the protagonist, a specific trait, whether it’s a physical trait (like green eyes or a gap between their teeth), a personality quirk (perhaps they say “Gotcha!” a lot or ask tons of questions), or a hobby (a baseball enthusiast, someone who’s obsessed with trains, or maybe a kid who’s into Tiddlywinks). This will help them, your readers, differentiate and distinguish among a large cast of characters in their minds.

If you’re writing a chapter book series, I do recommend that you set a “time frame” around your series. For example, my books follow Farah as she moves from 5th to 6th grade. Having a frame like this can allow you to come up with “topics” for each book in the series.

What’s next on the horizon for you?

I’m working on a young adult novel about a Palestinian American girl who lives with her father, a junk collector, a fact she tries to hide. She’s in love with a boy who likes her but thinks of her as a friend, and she’s trying to earn enough money to attend an expensive writing program. Stay tuned…

Cynsational Notes

Susan Muaddi Darraj won an American Book Award and the AWP Grace Paley Prize for her short story collection, A Curious Land (University of Massachusetts Press, 2019). She also won the Arab American Book Award for her Farah Rocks series, the first chapter book series to feature a Palestinian American protagonist. Susan lives in Baltimore and teaches fiction writing at the Johns Hopkins University. She has three amazing children who inspire her every day. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram at @susandarraj.

Stephani Martinell Eaton holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts where she won the Candlewick Picture Book Award and the Marion Dane Bauer Award for middle grade fiction. She is represented by Lori Steel at Raven Quill Literary Agency. Connect with her at stephanimartinelleaton.com.