By Carol McAfee

Spotlight image by Taha on Unsplash

Today I want to talk to you about poetry.

You may not consider yourself a poet. You may be scared of poetry in the way I am wary of numbers and higher math, so much so that I would join the witness protection program to avoid them. But numbers aren’t really scary, and neither is poetry. You just have to spend time with poems to feel more at home with them.

So I’m here to tell you five cool things about poetry. I might even tell you some poetic techniques you can use to improve your prose. Now if someone could just get me a math tutor.

First Cool Thing: What is a poem? Nobody knows

This is a godsend for all of us. Since nobody can tell you what a poem is, if you say you’re writing one, you are! No one can judge you. If they think your poem is bad, just tell them they don’t understand your oeuvre. Nobody knows what an oeuvre is either, so it tends to halt conversation in your favor.

While it’s hard to define what a poem is, we all have a general idea. A poem tends to be small, focused, concentrated. It concentrates on feelings and images and rhyme and rhythm. And it sounds good.

Here’s what a poem is, to me:

Poems are telegraphs from the soul

Poems offer us one truth

One moment, one mood

One illumination, one epiphany

A crystallization of feeling

A pizza of feelings

A healthy apple of feelings

A gigantic hot fudge sundae of feelings

Poems offer us compression

Distillation

Poems are inky black letters drowning of loneliness in a sea of white space

Poems are truth and beauty and serious stuff. Poems can giggle.

Poems are pleasing to the ear

Poems are Jack and Jill went up the hill

Poems are small things that indicate big things

Poems are power naps

Poems are tiny cups of Espresso

Poems are ants transporting Grand pianos on their backs

Poems are a single shell from the beach you can hold in your hand.

(Please note, and free chocolate bars to any who noticed—I’ve told you about poetry in the form of a poem.)

Second Cool Thing: Poems are Amphibians

The second cool thing about poems is (if you’re still leaning toward the witness protection program) you don’t have to write them at all. But you can use aspects of poems, which (for utter lack of imagination) we’ll call “poetic techniques.”

a) Poetic techniques are amphibians—you can use them in both your poetry and your prose. There are three poetic techniques I would like to talk to you about—Repetition, Metaphor, Rhyme—but that’s too easy, so I would like to complicate things and mention that these techniques only work if they come under the Fitzgerald Umbrella.

b): The Fitzgerald Umbrella

The Fitzgerald Umbrella is my phrase for something I learned from F. Scott Fitzgerald. And before we go on (notice my lowered voice because I am quite serious here), I want you to know what the author means to me. I remember going on a high school road trip and hiding away in the way back of the station wagon filled to the brim with my classmates and our history teacher on our way to the Big Apple. I was dorkily reading F. Fitzgerald’s short stories all by myself because I was shy and also my mom had a drinking problem and it helped to read Fitzgerald because he could write about his own drinking with the soberest eye, and it broke my heart, in a good way.

But, anyhow, what I took away from Fitzgerald is a phrase I want to give to you.

The phrase is: “the splendor and the sadness.”

The phrase comes from This Side of Paradise (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920), a poem called “Princeton—The Last Day,” and it goes like this:

…this midnight I aspire

To see, mirrored among the embers, curled

In flame, the splendor and the sadness of the world.

And it came to me, that phrase expresses what we’re trying to do as writers. We are trying to express what it is to live. And I think life is not just sad and not just happy but some kind of combination. And I think great writing reflects this. So what I always aim for, in whatever I write—I try to express that truth, that “splendor and sadness” of what it is to live.

(And again, cheers and more chocolates to those of you who noticed that I tried to give you some of Fitzgerald’s splendor and sadness right here in this section. The sadness: my mom’s drinking. And the splendor: my soul connecting with the soul of another—Fitzgerald.)

Third Cool Thing: Repetition

Repetition can be musical and fun, as in Chicka Chicka Boom Boom by Bill Martin Jr. and John Archambault, illustrated by Lois Ehlert (Simon & Schuster, 1989), as in Mem Fox’s The Magic Hat, illustrated by Tricia Tusa (Harcourt, 2002): “Oh, the magic hat, the magic hat! It moved like this, it moved like that!”

Repetition can amplify significance/create a solemn moment.

Think of Martin Luther King Jr.’s I have a Dream speech:

“I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be engulfed, every hill shall be exalted and every mountain shall be made low…”

I have a dream, I have a dream… There is a sort of theology to the repetition here. A pointing to the ineffable beyond. Ursula LeGuin speaks of this in her wonderful Steering the Craft (HMH, 2015). Repetition can “give the words their due majesty and power” she says. Repetition makes something “mean more,” makes something “gather weight.” Repetition points toward the sacred.

Finally, with repetition, we can speak to Fitzgerald’s “splendor and the sadness” of the world.

Take, for instance, Shakespeare’s famous line from Macbeth: “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.” Shakespeare uses the poetic cadence of repetition to both underscore tragedy and yet contradict it at the same time. Shakespeare drives the sorrow into us—”tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow”—and yet, in those same words, like an incantation, he drives it away.

In Hatchet (Bradbury, 1986), Gary Paulsen uses the poetic beauty of repetition to make us sad and yet comforted. Brian is lost and alone, struggling to survive in the Canadian Northwoods. After the search plane fails to spot him, Brian is plunged into the greatest despair he will ever feel. Yet, through poetic language, Paulsen suffuses that despair with hope:

He could not play the game without hope; could not play the game without a dream. …(T)here was nothing for him now. The plane gone, his family gone, all of it gone. They would not come. He was alone and there was nothing for him.

There is such unity and grace in these sentences that they themselves—the sound of them, so pleasing to the ear—achieve a kind of hopefulness, a kind of affirmation. The words “he could not play the game” said twice. The word “gone” struck three times, like the tolling of a bell. The words “nothing for him” said only once, seemingly forgotten, only to be resurrected at the end, in the paragraph’s final line.

In other words, the art of repetition can give us Fitzgerald’s “splendor” and “sadness.”

Fourth Cool Thing: Metaphors are the Mitochondria of the Soul

Remember high school biology? There, Mr. Robinson said to our class: “Mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell.” This is a metaphor. Mr. Robinson was comparing two unlike things: “mitochondria” and “powerhouse” to illuminate meaning. I don’t remember anything else from high school biology, I don’t even remember what mitochondria are, except you draw them like hot dogs laced up and down with mustard. But I will always remember they are the powerhouse of the cell. So metaphors can be powerful. They can be your new best friends. With metaphors, you can highlight moments in your books where you really want to create emotional resonance with the reader.

“Grief is a house” is a metaphor Jandy Nelson touchingly employs in her novel The Sky is Everywhere (Penguin, 2010) to help us experience Lennie Walker’s grief upon losing her older sister, Bailey. The metaphor of “house” works brilliantly to illumine how grief infiltrates our daily domestic lives, down to the walls, the mirrors, the chairs, the knocks on our door.

Grief is a house

where the chairs

have forgotten how to hold us

the mirrors how to reflect us

the walls how to contain us…

In A Single Shard (Clarion, 2001), Linda Sue Park tells the story of Tree-ear, a 12th century Korean orphan who lives with his disabled friend Crane-man under a bridge in a village of clay potters. Park’s exploration of brokenness and wholeness is orchestrated in metaphor, in both the names of Park’s two main characters—Tree-ear and Crane-man—and in the title itself.

As to her characters, “Tree-ear” is a hungry orphan who must put his ear to the ground and keep up with town gossip to learn where the most promising garbage dumps are —he is more “ear” than boy. And his friend Crane-man has a perpetual limp; it is his leg, rather than his ear, that defines him. The words “Tree-Ear” and “Crane-man” are repeated over and over in the course of the narrative. And what do these names mean to us? An ear, a leg—these are body parts, only parts of a whole. These “fractured” names subliminally shade our perception of Tree-Ear and Crane-Man as being broken, as being shards, parts of something, but not whole.

The title, A Single Shard, refers to a masterpiece of Celadon pottery that has been shattered and lost save for one single shard. Only that one shard of Celadon artistry exists in the world, one shard, one piece, and yet that broken piece is so striking, the potter of that vase is awarded an artistic commission.

Thus, the names Tree-ear and Crane-man, and the title A Single Shard, are metaphors that communicate Park’s theme that small things (such as tiny Tree-ear, or that one piece of pottery) can do big things. A piece or a part of something can act so powerfully, it can stand-in for the whole.

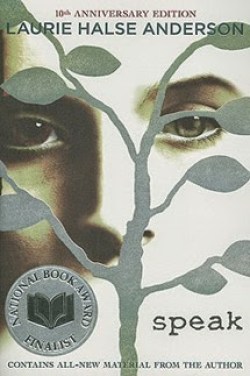

In her trail-blazing young adult novel, Speak (Square Fish, 1999), Laurie Halse Anderson tells us the story of a girl, Melinda, who is sexually assaulted at a summer party before high school. Because Melinda’s trauma has left her all but mute, Anderson chooses Trees as a brilliant metaphor to speak for Melinda until she learns once again how to speak for herself.

Trees are so prominent in Speak, they are even featured on the book’s front cover. We see the face of a girl—one eye brown, one eye green—peering out at us from behind the almond-shaped leaves of a silver tree. The girl is mysterious, partly because of that tree. Her spirit and the tree’s spirit seem entwined. And so that is the metaphor—Melinda is like a tree.

But why trees? Trees are powerful symbols. In many of the world’s mythologies and religions, trees represent growth, death, and rebirth. Trees, then, offer Anderson a potent way to illustrate Melinda’s spiritual near-death and renewal. On a craft level, Anderson needs her trees or something like trees, to speak for Melinda because Melinda is simply not speaking herself. True, we are in Melinda’s head because she’s our narrator, and true, we hear her voice, in that way. But in terms of dialogue and verbal interaction with others, Melinda is silent. This silence presents Anderson with a challenge. How to reveal Melinda to us? Trees offer Anderson a way to show us the changing seasons in Melinda’s heart.

It might have been odd to be in the mind of a girl with trees on the brain, spouting tree metaphors every five seconds. Anderson cleverly side-steps that problem by framing Melinda’s preoccupation with trees as a natural response to her year-long assignment from Mr. Freeman in art class. All students are to fish out a scrap of paper from Mr. Freeman’s broken globe. Melinda picks the word “Tree.” Mr. Freeman instructs his students to turn the object they chose into a work of art. This work of art must have so much feeling behind it, it will speak to everyone who sees it.

And so, in Speak, trees take root everywhere. They sprawl in happy profusion, from the trees Melinda tries to draw and paint and carve into linoleum to the real oak tree that needs pruning outside Melinda’s bedroom window. All these trees—their seeds, their branches, their leaves—evoke the emotional landscape of Speak and reveal to us Melinda’s growth and rebirth.

Fifth Cool Thing: Rhymes, A Love Story

Before we talk about love, I want to remind us of Fitzgerald’s splendor and sadness. How those words seem to encapsulate what good writing is about. You know how book blurbs say things like This book made me both laugh and cry. Or, this book broke my heart and stitched it together again. It seems that life is full of this dichotomy of sad/happy, dark/light. Rhymes can help balance out a poem, and give it light.

The truth about rhymes: Every rhyme tells a love story. When words rhyme, they yearn to be together. You create a longing in the reader for the rhyme, you create a home inside the poem for that one word and its mate. The rhyme, because it’s so pleasing to the ear, offers affirmation and optimism, even in the face of death. It offers the writer the chance to evoke life in all its complexity, to evoke what Fitzgerald called “the splendor and the sadness” of the world.

Dylan Thomas wrote a poem you probably know, “Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night,” which describes his witnessing his father’s death. Thomas is angry and grief-struck. And so here is the “sadness” Fitzgerald is talking about. But the way Thomas expresses his loss, with such fierce defiance, carries a note of triumph, and part of that triumph is that there is still order in the world, there are still words that belong together, there is still beauty, there is still love.

To accomplish this note of triumph, this affirmation of life over death, Thomas chose to write a particular kind of poem called a villanelle. The villanelle’s structure gives order to the poem and thus points to structure in the universe, a comfort in the face of death. There are 19 lines in the poem, the first five stanzas have three lines and the final stanza has four. The alternating lines rhyme with one another, telling a partial love story, but it’s the final stanza that makes us feel the triumph of life over death.

In that final stanza, Thomas brings his two most powerful lines together, which, like lovers, have been kept apart, stanza after stanza: “Do not go gentle into that good night/Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” The union of these two rhyming loves, “night” and “light” – this marriage of words that have yearned for one another and belong together—this is where Thomas rides out on a note of triumph; he leaves us with a kind of affirmation or optimism that is a wonderful counterpart to death and evokes “the splendor and the sadness” of the world.

Cynsational Notes

Carol McAfee writes about resilient kids and teens from broken homes. A graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, Carol recently completed her middle grade novel in verse, My Name is Max, about a boy, a girl, and a robot lost in the Maine wilderness. She is currently at work on Tobacco Creek, a young adult where, during a Civil War reenactment, sixteen-year-old Zoey falls in love with a time-traveling Union soldier.