|

| Yona Zeldis McDonough |

I hate weapons, especially firearms. Always have, and always will. Even the sight of a legally sanctioned gun—police office, hunter—makes me recoil and I literally take a step back.

Along with hating weapons, I hate war and though I concede that some wars have been necessary, I fail to see warfare as heroic or noble.

So when Scholastic tapped me to write a book about the evacuation at Dunkirk [of World War II.], I had to think long and hard about whether I could do it.

First, I had to read more about what happened, since I had only the vaguest notion of the history.

What I learned was somehow reassuring. Dunkirk was not a battle in which men and boys were hurt and killed. It was an evacuation—a retreat whose aim was simply to get out alive.

And it was carried out not by soldiers or sailors, but by ordinary citizens who heeded the urgent call.

Brave civilians rolled up their sleeves and took boats intended for fishing, rowing, pleasure across the English channel to the French beach where the boys were stranded. They either brought the boys back home, or ferried them to larger ships that did the job.

|

| Soldiers boarding a sailboat at Dunkirk |

This massive endeavor was called Operation Dynamo and it was responsible for saving 338,326 English and French soldiers.

Now here was a story I could get behind, and bring to life.

I said yes to Scholastic and settled down to work.

|

| Courageous (Scholastic, 2018) |

But even though the overall story was not one of battle or carnage, my editor at Scholastic let me know that I was expected to include scenes of battle, as well as action and drama.

How was that going to align with my anti-war sentiments?

First, I decided that neither of my two main characters—Aidan and his older brother George—were not going to handle weapons or kill anyone intentionally.

This was not too hard with Aidan—he was only twelve. But George was a soldier, and soldiers are trained to kill their enemies.

Yet I made a point of keeping guns out of George’s hands.

When he is face to face with a German soldier on a barge, the two scuffle and the German is thrown overboard by accident. It’s indicated that he might drown, but not explicitly stated.

More significant, I felt, was the scene in which a German solider is shot, though not by George, who instead pushes another soldier to the ground, thus saving his life. The other soldiers in the unit swarm the body, eager to strip the dead man of his gun, his boots and his jacket.

George remains apart, and is therefore able to notice the wallet of the dead boy, which has been thrown to the ground.

He picks it up and when he’s alone, examines its contents. He finds an ID card, with the boy’s name, Gerhardt, and age—18, a year younger than he is. He also sees photographs, presumably of Gerhardt’s parents and girlfriend.

|

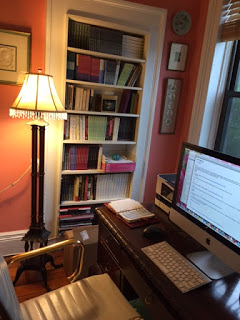

| Yona’s workspace |

Looking at these things, George realizes that the young German soldier who was killed was not some nameless, faceless enemy.

He was a person whose death will rip a hole in the lives of all those who loved him—parents, sweetheart, relatives, friends, teachers, neighbors.

George keeps the wallet and later in the book, he makes an important decision about what its future will be.

I let George’s realization about the true price of war speak for me, and it is my hope that readers of this book will take this understanding away with them when they close its covers.

Cynsational Notes

Yona Zeldis McDonough’s The Bicycle Spy (Scholastic, 2016) was named a Sydney Taylor Book Award Notable Book by the Association of Jewish Libraries. See a previous Cynsations post from Yona.

Fascinating plot, Yona. Congrats. I love your workspace. Is it always that tidy?

it sounds an amazing book. And I hope smart readers feel the spirit of the words. I would love to read it as well. thanks for sharing.