|

| Michelle Cusolito and Casey W. Robinson, debut picture book authors. |

By Traci Sorell

Today we welcome two of my fellow Epic Eighteen creators, Michelle Cusolito, author of Flying Deep (illustrated by Nicole Wong, (Charlesbridge, 2018)) and Casey W. Robinson, author of Iver and Ellsworth (illustrated by Melissa Larson (Ripple Grove Press, 2018)).

Both Michelle and Casey devoted time and effort to developing their skills before landing their first book contracts and shared some of their best resources.

Michelle Cusolito

I appreciated Michelle’s use of second-person narrative in her debut nonfiction book and how it draws the reader into the voyage.

Nicole’s digital illustrations show the wonders of deep sea exploration, both inside and outside the deep-sea submersible.

I’m excited to learn more about her involvement in the world of children’s publishing.

Michelle, describe your writing journey from a beginner level to published author?

When I first decided to pursue writing for children, I took a class on picture book writing taught by Lyn Littlefield Hoopes.

I had been an elementary teacher for a decade and had read thousands of children’s books, but I didn’t understand the ins and outs of picture books.

I had been an elementary teacher for a decade and had read thousands of children’s books, but I didn’t understand the ins and outs of picture books.

Lyn taught us about the basic structure, including the 32-page format and word counts. Lyn built a supportive community that nurtured me in those early years.

I also read thousands of published picture books and learned which publishers published which kinds of books.

I read The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Publishing Children’s Books by Harold Underdown (Alpha Books, 2008), Writing Picture Books: A Hands-On Guide from Story Creation to Publication by Ann Whitford Paul (Writer’s Digest Books, 2009; updated edition now available), Picture This: How Pictures Work by Molly Bang (Chronicle Books, 2016), and Writing with Pictures: How to Write and Illustrate Children’s Books by Uri Shulevitz (Watson-Guptill, 1997).

I studied the Children’s Writer’s & Illustrator’s Market (Writer’s Digest Books, yearly) and joined SCBWI, all while continuing to meet with the group started in Lyn’s class.

At a certain point, however, I needed more critical feedback of my work in order to grow. There were no critique groups in my area, so I started a SCBWI critique group. It took a several years to establish a functioning group, but eventually, a solid group formed.

We meet in person every month. My crit group pushes me to be a better writer. They help me identify the strengths of my manuscripts and are direct about what isn’t working. We celebrate each other’s accomplishments and commiserate over rejections. I would not have survived this journey without them.

Another group that has been important to my growth and learning is Julie Hedlund’s Picture Book 12×12.

Another group that has been important to my growth and learning is Julie Hedlund’s Picture Book 12×12.

When Julie started this challenge, she had the goal of writing 12 picture book drafts in a year. I knew I would never write that many. I am a notoriously slow writer, but I welcomed the support, camaraderie, and the chance to learn.

The monthly webinars alone are enough to make membership worth it. But what I most love is the unconditional support provided by our 12×12 community.

What is your relationship to the children’s-YA writing and illustration community? To the larger children’s-YA literature community?

This has been a long, sometimes difficult, journey. I got my first “good” rejections in 2008 (meaning, hand-written notes from editors) and my first book is coming out a decade later.

How did I survive it? I relied on the support of friends and family when I was feeling down. I celebrated every little accomplishment. I learned from others. I cried. I “got back on the horse.” (I still have to do all of those things… as of now, I have not sold a second book. The persistence and hard work continues).

I am lucky to have many connections and friendships in the kid-lit community. My earliest connections were all real-life ones made at the New England SCBWI Conferences. In the beginning, I knew no one. By my second conference, I knew a few people.

Now, I know so many people I get 15 hugs before I even reach the registration table. I love reconnecting with peers, talking shop, and simply being with my “tribe.”

Since social media came into wider use, I have also made connections all over the world through Facebook and Twitter in general, but also via “Picture Book 12×12,” and “KidLit 411” specifically. For the past several years, I have also been facilitating a craft/creativity book discussion for 12×12. Being part of the kidlit community also means learning together.

As an author-teacher, how do your various roles inform one another?

My life as an author has lots of overlap with my former life as a teacher. One of the traits I tried to nurture in my students is a sense of wonder and curiosity about the world.

What does that have to do with my life as an author? That same sense of wonder is what drives all my writing. I write about things I’m curious about. Things I want to learn more about. Things I want to share with kids to make them say, “Whoa, that’s so cool.” Or, “I wonder if I could do what that person did?”

|

| Michelle and students on an Alvin tour. |

Flying Deep was born in my classroom, though I didn’t know it at the time. I met a former Alvin pilot through a friend. I was fascinated by his stories of diving two miles below the ocean’s surface and knew my students would be, too.

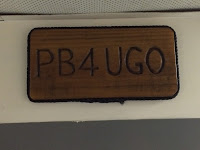

I invited him to visit our classroom. He shared slides of black smokers, giant clams, and six-foot tube worms. He told stories of fish that would explode if brought to the surface. And he told us Alvin pilots and scientists were reminded by a sign on-board the ship to “PB4UGO.” (There’s no toilet on board Alvin. Read Flying Deep to learn what they do).

I invited him to visit our classroom. He shared slides of black smokers, giant clams, and six-foot tube worms. He told stories of fish that would explode if brought to the surface. And he told us Alvin pilots and scientists were reminded by a sign on-board the ship to “PB4UGO.” (There’s no toilet on board Alvin. Read Flying Deep to learn what they do).

My students were fascinated and so was I.

Years later, while brainstorming possible topics to write about during PiBoIdMo (now called Storystorm), I thought about Alvin. I still had lots of questions. I decide to follow my curiosity and learn enough to write the book I wish I’d had in my classroom all those years ago.

Casey W. Robinson

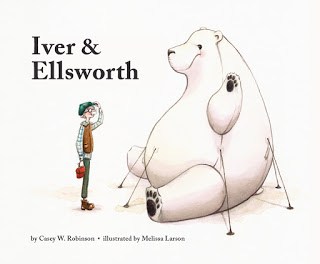

In my prior career, I worked with Native American elders, so I’m sensitive to how older people are portrayed especially to children and teens. Reading Iver and Ellsworth, my heart filled with gratitude because the beautiful text and intricate illustrations show young readers a positive representation about aging, transitions and friendship.

I know they’ll also enjoy discovering the gorgeous case wrap and examining the wordless spreads. So I’m happy to visit with Casey about her path to publication.

I know they’ll also enjoy discovering the gorgeous case wrap and examining the wordless spreads. So I’m happy to visit with Casey about her path to publication.

Casey, what first inspired you to write for young readers?

I’ve always been a writer, but it took me a long time to find my way to writing for children.

As an undergrad English major, I was both surrounded by novels and keenly aware that I was not a natural novelist. I was not a plot person; I preferred singular moments, a character’s emotion, and poetry.

I had difficulty meeting the page requirements assigned by professors (too few words!). In my mind, I mistakenly believed this meant I could never write books.

By the time I turned age 40, I had read more picture books than I could count to my three young daughters. I loved picture books.

One day it dawned on me that picture books were poetry. Picture books were often character driven. Picture books relied on few words — they dazzled because they did so much with so little. It turned out all the time I thought I’d been compensating for a deficit, I’d actually be honing a skill.

Please describe your pre-publication craft apprenticeship. How did you take your writing from a beginner level to publishable?

Once I’d made up my mind to focus on writing picture books, I decided I’d better learn everything I could about the craft. I started with a three-hour “boot camp” seminar on writing picture books offered at a local bookstore through the Boston writer’s group, GrubStreet.

I joined Julie Hedlund’s 12 x 12 Picture Book Writing Challenge where I connected with other picture book writers and gained access to industry professionals who talked about how they decided what should be published.

I joined Julie Hedlund’s 12 x 12 Picture Book Writing Challenge where I connected with other picture book writers and gained access to industry professionals who talked about how they decided what should be published.

I made weekly trips to the library and devoured as many picture books as I could. I started attending local SCBWI meet-ups and asking fellow authors about their journeys, favorite craft books, research tips and conference recommendations.

I attended an inspiring SCBWI-NY conference and met a woman who has since turned out to be a trusted critique partner.

Because I’m not an author-illustrator, I wanted to understand how the words worked without illustration – so I began re-typing the text of my favorite picture books into Word docs.

I studied the author’s word choice, their cadence and brevity, the line and page breaks. I noticed what was on the page and what wasn’t. I started to see how a writer creates room for an illustrator to take hold of the story. All the while, I kept writing.

After I had a few completed manuscripts, I started signing up for 15-minute critiques with agents and editors offered through The Writers’ Loft in Sherborn, Massachusetts.

After I had a few completed manuscripts, I started signing up for 15-minute critiques with agents and editors offered through The Writers’ Loft in Sherborn, Massachusetts.

Looking back on this, I’m a bit embarrassed at what I asked those kind professionals to review (my early manuscripts were so bad!). But that kind of professional feedback was gold.

I learned an incredible amount about character development, story arcs, and how layering meaning and subplots can create depth and enrich the picture book experience. I did all of these things for a year and a half before I wrote my first manuscript worthy of submission.

As an unagented author, how did you identify your editor and connect the manuscript with the publishing house?

I found Rob Broder and Ripple Grove Press through Julie Hedlund’s 12 x 12 Picture Book Writing Challenge. 12 x 12 offers monthly webinars with industry professionals and in his webinar, Rob discussed what Ripple Grove looks for in submissions. He talked about what books inspired him to start his own imprint to bring more picture books into the world.

One book he mentioned was Philip C. Stead and Erin E. Stead’s A Sick Day for Amos McGee (Roaring Brook Press, 2010), which has a similar feel to Iver. After listening to his talk, I had a hunch that Iver might be a good fit.

So, I submitted to Ripple Grove. Eight weeks later, we were discussing revisions and a contract.

How are you approaching the transition from writer to author in terms of your self-image, marketing and promotion, moving forward with your literary art?

Finding regular writing time is by far my biggest challenge. I’m trying to carve out time in the wee mornings before my three kids wake up and before I start my full-time job as a marketing director.

I keep a running list of book-related marketing to-dos, so that when I have a few minutes I can cross something off the list.

I keep a running list of book-related marketing to-dos, so that when I have a few minutes I can cross something off the list.

I am often muttering to myself “one thing at a time, one thing at a time” so I don’t get overwhelmed by all that I could be doing.

As far as self-image, I’m a fairly private person so the shift to doing public book promotion and building more of an online presence has been a little nerve-wracking!

But then I remind how much how much the kidlit community lifts each other up in service of getting books of all kinds into the hands of kids – and that I am just doing my small part to further that important mission.

Most days, that’s all the motivation I need.

How did the outside (non-children’s-YA-lit) world react to the news of your sale?

Much celebration! I’ve been blown away by how creatively people have cheered alongside me.

(The pics show a stuffed Ellsworth bear made to accompany me at book signings & Iver made of sculpey clay!)

Along with the celebrating, I’ve had a number of conversations with people outside the industry that helped me realize how deceptively simple picture books appear to be to write.

Most of us don’t share publicly the inner turmoil of trying revision after revision, of shelving a great-character-but-no-plot manuscript or granting more time to the seed of an idea that refuses to sprout. We don’t lament our hopes dashed by rejection, again and again.

So of course, from the outside the publishing process itself can also look simple.

Cynsational News

|

| Casey W. Robinson |

Casey W. Robinson grew up in Maine and now lives with her family just outside of Boston in a yellow house overflowing with books.

She occasionally drives past a rooftop bear in the nearby city of Worcester.

Iver & Ellsworth is her debut picture book. You can follow her on Instagram (@cwrobinson) and Twitter (@CaseyWRobinson).

|

| Michelle Cusolito inside Alvin |

Michelle Cusolito spent her childhood mucking about in the fields, forests, and swamps around the farm where she grew up in southeastern Massachusetts.

As an exchange student in high school, she temporarily traded rural living for city life in Cebu, Philippines. These early experiences set her on her current course exploring nature and culture like the locals.

She spent 10 wonderful years as a grade 4 teacher. Now, when she’s not mucking around in the world, she’s usually in her office or local coffee shop weaving these experiences into stories for children.

Traci Sorell covers picture books as well as children’s-YA writing, illustration, publishing and other book news from Indigenous authors and illustrators for Cynsations. She is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation.

Traci Sorell covers picture books as well as children’s-YA writing, illustration, publishing and other book news from Indigenous authors and illustrators for Cynsations. She is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation.

Her first nonfiction picture book, We Are Grateful: Otsaliheliga illustrated by Frané Lessac (Charlesbridge, 2018) features a panorama of modern-day Cherokee cultural practices and experiences, presented through the four seasons. It conveys a universal spirit of gratitude common in many cultures.

In fall 2019, her first fiction picture book, At the Mountain’s Base, illustrated by Weshoyot Alvitre will be published by Penguin Random House’s new imprint, Kokila.

Traci is represented by Emily Mitchell of Wernick & Pratt Literary Agency.

Thank you for hosting us, Cynthia and thank you for the interview, Traci.

Wonderful interview from two fabulous debuts! I am so happy to have your books on my shelf. Well done!