By Amy Bearce

One thing I learned while earning my Masters of Library Science and my school librarian certificate is that if you try to censor a book, librarians will Take. You. Down.

|

| “Don’t make me get my gloves out.” (Boxing Glove by Janusz Gawron via freeimages.com.) |

Censorship and First Amendment rights are hot-button issues for librarians. Prior to my degree, I had no idea, but I loved it: librarians as righteous warriors for freedom of speech! Yes!

However, I write mostly upper-middle grade stories. For me, this means walking that fine line between being honest without censoring and also keeping in mind the needs of my tween and young teen readers. It’s a tough call sometimes.

|

| “Balance is necessary.” (Tightrope Walker by Kristin Smith via freeimages.com) |

The American Library Association says:

“Constitutionally protected speech cannot be suppressed solely to protect children or young adults from ideas or images a legislative body believes to be unsuitable” (2008).

However, school librarians, like teachers, are seen as “in loco parentis,” giving them a unique responsibility to protect their students’ emotional and physical well-being (Chapin n.p; Duthie 91, Coutney, 18). At the same time, school librarians are also charged with defending their students’ First Amendment right to intellectual freedom.

As it turns out, this dual role of the school librarian is a good representation about how I feel about my role as a writer for tweens and young teens. I want to both help young people think about new ideas and push boundaries while honoring their age and maturity levels.

I am strongly anti-censorship, but when I was revising Fairy Keeper (Curiosity Quills, 2015) after graduating with my library science degree, I decided to focus on the needs of my target audience.

When my publisher and I decided my book would work better as an upper-middle grade novel, not YA, I wanted certain things in the story to be tempered. Not changed, not faked—just softened, without sacrificing any excitement or edginess.

When my publisher and I decided my book would work better as an upper-middle grade novel, not YA, I wanted certain things in the story to be tempered. Not changed, not faked—just softened, without sacrificing any excitement or edginess.

Tweens and young teens can be incredibly worldly and savvy, but still easily bruised.

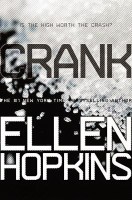

Because of this reality, some elementary and intermediate schools with fifth graders will carry Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins (Scholastic, 2008) while others will not. Some middle school libraries will carry Crank by Ellen Hopkins (Simon Pulse, 2004). Others will not.

The line between selecting age-appropriate books and self-censorship truly is a blurry target. There are so many excellent books, with a huge range in how those books handle difficult topics.

As a writer, I took note. Was I censoring myself, or was I choosing material wisely for my audience?

Let me be clear. I’m not advocating avoiding difficult issues such as death, drugs, or violence. Tweens and teens can handle a lot and don’t need rainbows and unicorns.

|

| “Although who wouldn’t want a rainbow unicorn?” (Unicorn by Sarah at Totally Severe via Flickr.com.) |

But I now approach those topics very thoughtfully when writing for middle grade readers, even at the upper middle grade range. Some writers will feel okay including topics others might not— just as some school libraries carry books others don’t.

What it boils down to is: know your readers. This is true for librarians, but also for writers. When I write now, my students from the library are in the back of my mind. The books I’ve read are there, too, whispering what’s been done, what worked, and what didn’t work.

And hopefully, all of that has resulted in a stronger story, because I’m not just writing for the heck of it. I want to connect with my readers. And that means they deserve some special consideration as a group of people in their early adolescence, a group of people that I’m proud and thrilled to write for.

About Amy

|

| Amy Bearce |

Amy writes stories for tweens and teens. She is a former reading teacher who now has her Masters in Library Science along with a school librarian certification.

As an Army kid, she moved eight times before she was eighteen, so she feels especially fortunate to be married to her high school sweetheart. Together they’re raising two daughters and are currently living in Germany, though Texas is still where they call home.

A perfect day for Amy involves rain pattering on the windows, popcorn, and every member of her family curled up in one cozy room reading a good book.

About Fairy Keeper

|

| Excerpt |

Most people in Aluvia believe the Fairy Keeper mark is a gift. It reveals someone has the ability to communicate and even control fairies.

Fourteen-year-old Sierra considers it a curse, one that binds her to a dark alchemist father who steals her fairies’ mind-altering nectar for his illegal elixirs and poisons.

But when her fairy queen and all the other queens go missing, more than just the life of her fairy is in the balance if Sierra doesn’t find them. And Sierra will stop at nothing to find them, leading her to a magical secret lost since ancient times.

The magic waiting for her has the power to transform the world, but only if she can first embrace her destiny as a fairy keeper.

Fairy Keeper is now available in paperback and e-book.

Cynsational Notes

American Library Association. “Free Access to Libraries for Minors; An Interpretation of the

Library Bill of Rights.” 2008. Web. 18 July 2012.

< http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/librarybill/interpretations/freeaccesslibraries>.

Chapin, Betty. “Filtering the Internet for Young People: The Comfortable Pew is A Thorny

Throne.” Teacher Librarian 26.5 (1999): 18. Library Literature and Information Science Full Text. Web. 17 July 2012.

Coatney, Sharon. “Banned Books: A School Librarian’s Perspective.” Time U.S. Sept 22, 2000.

Web. 17 July 2012.

Duthie, Fiona. “Libraries and the Ethics of Censorship.” Australian Library Journal 59.3 (2010):

86-94. Library Literature & Information Science Full Text. Web. 17 July 2012.