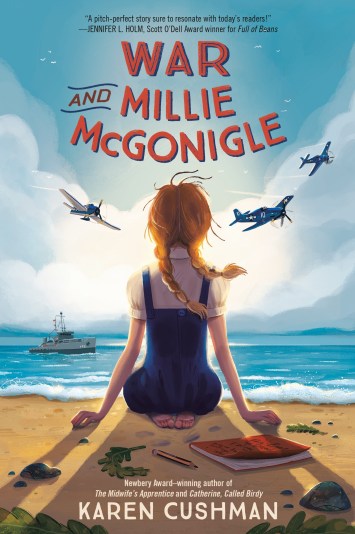

Today we welcome Karen Cushman to Cynsations. She is the author of Newbery Medal winner The Midwife’s Apprentice (Clarion, 1995), the Newbery Honor book Catherine Called Birdy (Clarion, 1994) among many other prize-winning historical fiction novels. Today Karen will talk to us about her newest book, War and Millie McGonigle (Knopf, 2021).

Congratulations on the release of War and Millie McGonigle. Tell us about how this book came to be.

For more than fifty years, I heard my husband’s stories about growing up on the bay side of San Diego’s Mission Beach, long before it was dredged and turned into a popular resort. The warm bay water lapped at the sand when the tide was in. There was swimming and surfing, and children went without shoes from June until September, and their feet grew calloused and summer wide.

Phil would row his small boat out and read comic books until his nose was sunburned and his empty stomach growled. He watched seals tumble in the water and fished for perch and small halibut. When the tide was out, the beach was mud, pocked with pickleweed and eelgrass. Shoals and small islands, home to colonies of mussels and sand dollars that stood on end in soldier-like rows, were revealed. And early in the morning, Portuguese fishermen would be out catching the octopuses whose hiding holes the ebbing tide had uncovered.

The place was idyllic for Phil, and for me as I listened to him. I wanted to write about it, to put someone there to be nurtured and soothed as he was by the tides flowing in and out, the fishy smell of the mudflats, the squawks of the gulls, the peace of the small waves on the bay, and the sparkle of the sun on the quiet blue water. So anxious, fearful, worried Millie was born.

I’ve heard you talk about your university research work on the material culture of children. First, will you tell our readers more about that type of research? And will you tell us how that research has influenced your writing?

Material culture is a term for the objects that people have made and used, the art they saw, the music and jingles and advertisements they heard. The study of material culture tells of the relationships between people and their things. Children’s material culture includes toys, clothing, cribs, strollers, and highchairs, and what they tell us about the children who used them and the culture that created them.

What kind of society wrapped children in swaddling clothes? Gave babies hard, heavy, embellished silver teething rings and rattles? Or guns and toy soldiers? Or heavily gendered clothing and books and dolls? I learned to read and interpret what objects made manifest about a people and a culture. When I write, I try to include those objects that might reveal a character, a place, or a time. What do they value? Ignore? Think worthless?

So many of your books are historical fiction. As you research, and material accumulates, how do you keep track of it all? Do you have charts, notebooks, spreadsheets?

For my early books, I kept well-organized notebooks divided by subject: setting, characters, language, clothing, and such. Then I moved to stacks of yellow sheets with notes scribbled on them. Now notes and drafts are dropped into a box, to be retrieved when I say Where was that quote about . . . ? or some such. I’ve gotten much better at remembering information, and my numerous reference books are always at hand. Now I just write with books stacked around me for quick reference and relevant sites bookmarked on my computer.

Reflecting on your personal journey (creatively, career-wise, and your writer’s heart), what bumps did you encounter, and how have you managed to defy the odds to achieve continued success?

The bumps I have encountered on my writing journey are mostly of my own making and came long before I started writing seriously. I was raised in the 1950s, when girls were not taught to think and create and follow dreams. I didn’t know anyone else who wrote and certainly no adult who wrote for a living, so though I wrote all the time for myself, I never planned to be a writer. I thought I’d be a secretary, maybe, or a teacher, or a school crossing guard, like my grandpa. I just wrote because it felt so good.

I wrote through high school and college, but after that I didn’t write anymore. I got married and had a daughter, moved up and down the West Coast, went back to school—twice—but I didn’t write.

I was waiting for magic, waiting to be transformed into a writer. In truth, I think that books and writing were too important to me to risk finding out that I couldn’t do it very well—or at all. So I didn’t even try.

After years of thinking up stories and doing nothing with them, I had an idea for a book about a girl in the thirteenth century. It intrigued me, but people told me to be prepared for failure, that first novels don’t sell, history is not popular with young people, that the Middle Ages are dead, and no one wants to read about girls anyway. However, I had a story to tell and it seemed important to me to tell it, no matter what happened, so I ignored everyone and just wrote. Why I was finally able to overcome my own insecurities and the negative statements of others, I don’t know. Maybe because I was nearly fifty and it was now or never!

So I just sat down and started to write, and Catherine, Called Birdy (Clarion, 1994) was born. What surprised me was the incredible luck I had in finding an enthusiastic agent (the first one I queried) and a fabulous publisher and editor and cover artist (and Trina Schart Hyman did my covers until she passed away). And I was surprised by the camaraderie, mutual support, and friendliness of everyone in the children’s book community. I had heard so many horror stories about the publishing world, but my experience was splendid in every way possible.

I recommend anyone with a book inside her just to do it. Take the leap and write, with passion and gusto and hope. It could change your life. It changed mine, and I haven’t had a bump since.

Which writers have influenced your writing the most?

The earliest historical novels I remember reading were Lois Lenski’s regional books Strawberry Girl (J.B. Lippincott, 1945) and Cotton in My Sack (J.B. Lippincott, 1949). I loved reading about ordinary girls like me in somewhat extraordinary circumstances. And now I write about them.

I depend on Ray Bradbury’s and Anne Lamott’s incredible books about writing, I love Ellis Peters and Rosemary Sutcliff, who demonstrate just how fine historical fiction can be, and Patricia MacLachlan’s Sarah, Plain and Tall (Harper & Row, 1985), which I think is a primer on how to write beautifully.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I was a shy, nerdy, bookish, introverted high school freshman. I knew everyone was more popular, sophisticated, and fun than I could ever be, but I was bright and clever with words. Autographed books were popular that year, and people noticed that I wrote funny things in their books and they remembered me.

Sometime later that year, we had a school trip to Disneyland, which had just opened. On the bus we started singing a “Hey, lolly lolly lolly” song that ended each verse with a clever rhyme for someone’s name. I was quick and good at it, and some of the students yelled out, “Let Karen do us all!” so I did.

And I was popular. Words did that. Language did that. I’ll never forget that feeling.

If you could tell your younger writer self anything, what would it be?

I would ask her what she is so afraid of. And I’d tell her that someday she’d be eighty and how would she feel if all those stories inside her never came out?

Cynsational Notes

Karen Cushman is the author of The Midwife’s Apprentice (winner of the 1996 Newbery Medal), Catherine, Called Birdy (a Newbery Honor book), The Ballad of Lucy Whipple (winner of the John and Patricia Beatty Award), and several other prize-winning novels published by Clarion Books. Karen lives and writes on Vashon Island in Washington state.

Karen and her husband along with SCBWI established the Karen and Philip Cushman Late Bloomer Award for authors over the age of fifty who have not been traditionally published in the children’s literature field.

Stephani Martinell Eaton holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts where she won the Candlewick Picture Book Award and the Marion Dane Bauer Award for middle grade fiction. She is represented by Lori Steel at Raven Quill Literary Agency.