|

| Curriculum Guide & Excerpt |

Joshua David Bellin is the first time author of Survival Colony 9 (McElderry, 2014). From the promotional copy:

In a future world of dust and ruin, fourteen-year-old Querry Genn struggles to recover the lost memory that might save the human race.

Querry is a member of Survival Colony Nine, one of the small, roving groups of people who outlived the wars and environmental catastrophes that destroyed the old world.

The commander of Survival Colony Nine is his father, Laman Genn, who runs the camp with an iron will. He has to–because heat, dust, and starvation aren’t the only threats in this ruined world.

There are also the Skaldi.

Monsters with the ability to infect and mimic human hosts, the Skaldi appeared on the planet shortly after the wars of destruction. No one knows where they came from or what they are. But if they’re not stopped, it might mean the end of humanity.

Six months ago, Querry had an encounter with the Skaldi–and now he can’t remember anything that happened before then. If he can recall his past, he might be able to find the key to defeat the Skaldi.

If he can’t, he’s their next victim.

How did you discover and get to know your protagonist? How about your secondary characters? Your antagonist?

|

| Joshua’s blog is YA Guy. |

That’s a great question, because my protagonist spends the entire novel trying to discover and get to know himself!

Querry Genn, the fourteen-year-old narrator of Survival Colony 9, suffers from traumatic memory loss brought on by an accident six months before the action of the book begins. He can’t remember the accident, and he can’t remember anything that happened before it.

This condition presented me with the opportunity to explore Querry’s past as he himself discovers it—to follow along with him as he slowly, painfully fits the pieces together.

When I was drafting, I produced a number of possible pasts for Querry, testing them out until I found the one I liked the most.

Of those that didn’t make the cut, I discarded the majority during the revision process—but others I retained as false leads that Querry himself ultimately discovers to be untrue. So readers are in some ways in Querry’s position, learning along with him what’s real and what isn’t—but just like him, they may jump to conclusions that aren’t borne out by later revelations.

Given my narrator’s amnesia, I was able to pursue a somewhat similar process with the other characters. Querry doesn’t remember anyone else either, so he has to reconstruct who they are and how they fit into his life. So with almost all of the secondary characters—Querry’s father, Laman Genn; Korah, the teenage girl he has a crush on; Yov, the teenage boy who torments him due to his disability—I had the opportunity to develop them in two not always congruent ways: who they actually are, and who Querry thinks they are. My hope is that readers will be drawn into the mystery of not always knowing who or what they can trust.

And that leads me to my antagonists, creatures I call the Skaldi. These monsters have the ability to consume and mimic human prey—which means you can’t be sure who’s human and who’s Skaldi in disguise. Taking all these factors together, I think readers will find the characters in Survival Colony 9 convincingly complex, mysterious, and full of surprises!

|

| Josh Bellin and Big Green, White Cloud MI, age 11 |

As a science fiction writer, going in, did you have a sense of how events/themes in your novel might parallel or speak to events/issues in our real world? Or did this evolve over the course of many drafts?

I knew from the start that Survival Colony 9 was going to speak to environmental issues. The world of the novel is a hostile desert, and that setting was one of the first things I envisioned.

When I started writing, the category of “cli-fi”—fiction having to do with climate change—hadn’t yet been coined, but it turns out that’s exactly what I was writing!

I will say, however, that it took a number of drafts before I was satisfied with how my novel spoke to contemporary events/issues. In early drafts, the environmental subtext was much more explicit: I devoted a whole chapter to one character explaining to Querry the history of their world, which meant, essentially, a huge truckload of exposition disguised as dialogue. It was too much, not only in terms of length but in the tone, which seemed far too didactic.

So I scaled way back, letting the scene speak for itself. It’s a desert world. Food and water are scarce. Violent, unpredictable storms pound the landscape.

If that image doesn’t speak to readers, no amount of exposition will.

I think this is an important point for science fiction writers, because science fiction is so topical it’s easy for it to become preachy.

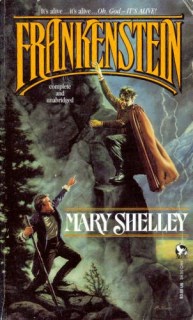

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), which some people consider one of the earliest sci-fi novels, raised all kinds of fascinating questions about the nature of life and the power of science—but it didn’t preach to its readers, didn’t tell them what to believe.

Yet when a much older and sadder Shelley revised her novel in 1831, she turned it into a long, boring sermon on the excesses of scientific experimentation. That’s why I never teach the 1831 edition, even though it’s customary to consider the most recent edition the most representative of the author’s vision.

I think Shelley violated her own best instincts as a fiction writer in 1831, and she produced a much inferior novel as a result.

I’m proud of the fact that I’m an environmentalist. I love the natural world, and I work hard—both as a father and as an activist—to instill that love in others.

But as a fiction writer, I’m not going to hit readers over the head with my beliefs. The role of fiction is to stimulate the imagination, not to proselytize or recruit. Having presented the best imaginary world I can, it’s up to readers to do with that world what they will.