Tony Abbott on Tony Abbott: “In brief, I was born in Cleveland, Ohio; and moved with my family to Connecticut when I was eight.

Tony Abbott on Tony Abbott: “In brief, I was born in Cleveland, Ohio; and moved with my family to Connecticut when I was eight.

“My father had a Jesuit college education (courtesy of the G.I. Bill, rightly touted as one of the most amazing pieces of legislation in the last century) and wanted to teach, so when he got his Ph.D., there were several choices of places to move to–as I recall, Detroit, a small town in Maine, or Connecticut. He and my mom chose the latter, a fairly new college, so we moved. He was a professor at the college, later university, there for 30 years.

“I went to the University of Connecticut, graduated with a degree in English, worked in bookstores, a library, and a technology-related publishing company before I married and had children. I always wrote: short stories and poetry (quite a bit, actually, some appearing in small magazines), but turned to children’s books after having children of my own, and reading to them.”

What first inspired you to write for young readers?

Reading to my first daughter (she was born in 1985) gave me a chance to learn about the wonderful books being written for children at that time. When I was growing up, it was either picture books (the Golden Age) or, for older readers, classics and Hardy Boys.

The market had grown from that time to the eighties. My daughter and I read constantly when she was very young: William Steig, William Joyce, the Fox books, the Cut-ups (which I still think are some of the funniest books ever written), many others, usually of a quirky sort. I became entranced with the idea of writing a book of this sort.

Could you please update us on your recent back list, highlighting as you see fit?

I suppose I am most proud of my novels, so I’ll start there. My first was scantily reviewed; Kringle (Scholastic, 2005) is a Christmas fantasy, a sort of hagiography written about the boy who became this monumental Winter Gift Giver (as some stories call him) that we commonly know as Santa Claus.

I suppose I am most proud of my novels, so I’ll start there. My first was scantily reviewed; Kringle (Scholastic, 2005) is a Christmas fantasy, a sort of hagiography written about the boy who became this monumental Winter Gift Giver (as some stories call him) that we commonly know as Santa Claus.

But I still love this book. It harks back to the classic English children’s stories from Peter Pan to The Hobbit, and was written as something like a saint’s biography, but with all the humor and adventure lacking from most of the classics in that genre.

To pitch it to Scholastic, I employed a crass phrase: “Santa Claus meets The Lord of the Rings.” In truth, that is fairly accurate, as I had long thought of the current idea of Santa Claus as something like the vulgarized remains of a once great hero on the scale of King Arthur or Odysseus. So I wrote the book (boy, am I spending a lot of time talking about this book no one knows!) as an homage to the hero I call Kringle.

There is a war, of course. Wherever there are elves, which the secular Christmas story always has, there are goblins, their natural enemies. I set this book in 410 AD Britain, as the Roman forces are leaving the island, leaving the way open for the goblins to rise from their (traditional) underground home. Kringle comes to lead the good elves against the goblins, and that’s the center of the story.

Along the way, I was able to work in some of real history of early Britain, and the actual Nativity story. What may seem a potpourri to some makes perfect sense to me, as this is how I celebrate the December holiday. Whew, enough of that.

More recently came Firegirl (Little, Brown, 2006), a novel that has its origins in a time in my own childhood that I never thought I would talk about, let alone write about. A burned girl came into my class when I was in sixth or seventh grade, and some things happened, little things that moved through the classroom. It took some forty years or more for this story to come out.

More recently came Firegirl (Little, Brown, 2006), a novel that has its origins in a time in my own childhood that I never thought I would talk about, let alone write about. A burned girl came into my class when I was in sixth or seventh grade, and some things happened, little things that moved through the classroom. It took some forty years or more for this story to come out.

There’s a bit to say about Firegirl, how the story changed in the writing of it from memoir-like to a piece of fiction, that moment all writers know when the inspiration is trumped (or set aside) by the novel’s own story and the characters that live in it, as opposed to the real people who may have inspired them.

Firegirl became quite its own tale, with inventions and imagined conversations, but with an eye always on what motivated me to write it in the first place.

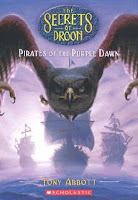

Over all of these has been the amazing experience of writing the series The Secrets of Droon (Scholastic, 1999-). I began writing these stories in 1997, and the first came out in 1999, so we are, at the time I’m writing this, nearing the 10th anniversary of the publication of these stories.

Over all of these has been the amazing experience of writing the series The Secrets of Droon (Scholastic, 1999-). I began writing these stories in 1997, and the first came out in 1999, so we are, at the time I’m writing this, nearing the 10th anniversary of the publication of these stories.

I like to think of this fantasy series for second graders and up, as a single, multi-thousand-page saga.

When a young reader starts these books, and continues with them, he or she is reading a very complex and many-charactered drama. An epic in installments.

I’ve been lucky enough to join a very small club in having so many books in a single series published. As I write this, I am writing my 40th book in the series. A mystifying achievement, even for me to consider.

Congratulations on the publication of The Postcard (Little Brown, 2008)(recommendation)! Could you tell us a bit about the book?

Jason’s grandmother, who has been ill with dementia for years, has just died. It’s the first week of his summer vacation at home in Boston, and he is asked/told to fly down to Florida to join his father in cleaning out his grandmother’s house, to sell. He doesn’t want to go, but his mother has to fly out of town for business, there is no one to take care of him, so he goes.

Once there, he sees a bunch of strange characters at the funeral, then, in the midst of the obligatory cleaning of her little house, discovers a piece of hard-boiled pulp fiction in an old magazine by a young writer, and its heroine appears to be his grandmother.

Finally, he discovers an old postcard in which he finds a clue, which he follows–only to find more of the pulp story. He reluctantly teams up with the girl who used to mow his grandmother’s lawn, and they find more and more of this story that brings them from the 1940s to the present day.

The Postcard is an experiment in storytelling (since the chapters of the old story are interspersed with Jason’s story), a family drama, a three-generation love story.

I have to say it became a rather bigger affair than I intended, but in a way it’s my favorite book; an homage to old Florida, to noir writing, and to young love.

What was your initial inspiration for the story?

The first impulse was the actual postcard. I collect linen postcards from the 1940s; I love their color, their artificiality.

It came to me one day as I was holding a particular card that someone from that era could have hidden a clue to something in the picture on the card that was so hidden no one had seen it for some 60 years. This stayed in the back of my mind.

When I was considering what novel I would follow Firegirl with, I had the notion of doing a thriller. It would involve a young artist, and I was not sure whether it was a children’s story or something different.

The more I pressed into the idea, the more I realized that it was not a pictorial artist, but a writer, and that it had an element of the past about it, and, finally, that I would have to write that writer’s story. This linked with the postcard/clue/mystery, and the basic part of The Postcard was born.

To make it work there needed to be the modern element, and quite soon after starting to sketch this out, Jason appeared to me. He was a boy whose family is in trouble; his parents’ marriage is rocky, and he’s stuck in the middle, which he realizes literally on the plane from Boston to St. Petersburg that is taking him away from his mother and to his father.

Rather than making the postcard be about some unrelated story, I knew it had to mean something to him in order for the book to work. It was then that the big pieces fell into play.

The postcard and its story reveal to Jason things about his grandmother and her first boyfriend that even his father didn’t know.

Because Jason discovers these things with Dia in both a comical and sometimes dangerous way, a relationship blossoms between them that positions itself with the relationships of his grandparents and parents.

If readers make it all the way to the end, they might seen a continuum there that was, I have to say, not quite a conscious thing while I was writing it. Other parallels were, of course.

What was the timeline between spark and publication?

How far back does one go? If I go back to the clue in the postcard, we’re probably talking six or seven years. The time I first mentioned “thriller” to my editor at Little, Brown, Alvina Ling, was probably about three and a half years, the late fall of 2004, before the book appeared.

In the spring of 2005, I began to write it down. Late in the summer, I submitted a brief draft to Alvina. She said keep going. The next spring (2006) I submitted a more complete draft. Alvina’s first editorial letter followed a couple of months later.

I produced another draft in the fall, followed by another editorial letter. Because it was a mystery that had two timelines (1944-1962 and the present), and because for mysteries to work they have to be completely water tight, there were a lot of revisions, back and forth for months, and even after the pages were typeset.

As writers who have tried a mystery know, the more complicated your plot is, the number of issues to resolve, the more work must go into simplifying the way it’s told.

What were the challenges (literary, research, psychological, logistical) in bringing it to life?

There were lots of challenges, substantial ones. The background of St. Petersburg, Florida, was taken a lot from memory. My grandmother lived there for some twenty years, and I relied on my experiences of visiting her from Ohio, first, then Connecticut, but I had to go down to do some on-the-ground research.

This is physical stuff, but it was quite enjoyable tracing the streets that Jason and Dia walk, the attractions they go to to find more parts of the story, and so forth.

I read a number of books about early Florida, and devised a character who was a real estate baron and railroad builder early in the last century; it’s fascinating to think of Florida’s comparatively recent history as a cross between wilderness and the wild west.

Peter Matthiessen has depicted this in his novels about the everglades. St. Petersburg was both wild and an early destination for celebrities, so the real history is rich.

Literarily, I found myself reading any southern author I could lay my hands on. I’m still under this spell (talk about riches!); my next series with Scholastic, The Haunting of Derek Stone (beginning January 2009) is set squarely in the Southern Gothic tradition (more below).

In any case, the experience of dealing with the physical effects of a person who has died is something I’ve had to do a couple of times, and to me it’s one of the most strangely intrusive, melancholy, burdensome, and profoundly joyful experiences you can have.

You come away from it with both a sadder but more hopeful view of this thing we call life. Jason’s journey from beginning to end is tinged not only with humor and love, but with that–the presence of death–as well.

You’re the author of The Secrets of Droon (Scholastic, 1999-) series! What are the challenges of series writing? What recommendations do you have for other writers?

From the practical to the spiritual, the series writer has a lot of balls to keep in the air. Or, as my wife says, dishes to spin.

From the practical to the spiritual, the series writer has a lot of balls to keep in the air. Or, as my wife says, dishes to spin.

You have to be the sort of person who doesn’t recognize the concept of “writer’s block.” It doesn’t exist; that’s all.

You have to be able to keep to a deadline (this is why newspaper writers were so successful in early Hollywood, one imagines, where the novelists had a poorer track record).

You have to be constantly inventive. The question, “where do you get your ideas?” has to be nonsensical to a series writer. You have to have a business side equal to your imaginative side, too, since series fiction tends to work in tandem with trends in the culture at large.

The down side, of course, is that the schedule of three or four books a year (or more) doesn’t allow staying with a particular story long enough to make it rich and deep and work on every level that you know you could make it work on. There are rough spots in language and plot that, with time, you could correct. But time runs out.

This is not an apology; I think series writing is crucial to the development of early reading as straight novel writing is not.

This is not an apology; I think series writing is crucial to the development of early reading as straight novel writing is not.

As someone who has been lucky enough to do both, I feel, as you would expect, that my best work will be in my novel writing, my “literary fiction,” but I don’t denigrate other kinds of writing.

Children’s publishing is a business, and there are many ways of engaging in it, to the benefit of the young reader.

As a reader, so far what are your favorite new children’s books of 2008 and why?

I have two so far, but I have to admit that I read very little children’s literature. I try to read my friends, but even then, I find my tastes are extremely narrow, so I give up easily.

Part of me thinks, and this may seem snobby, but I think it’s really a matter of the time allowed to us, part of me thinks that I should be reading the really fine writers because in addition to their superior art, they have the most to teach me.

It’s hard to spend time reading, for instance, a fantasy book, when I write the Droon stories, which are likely more involved. I guess that sounds bad, but so be it.

Two books this year, however, of the few I have read, I have really liked. One is Bird Lake Moon by Kevin Henkes (Greenwillow, 2008), a lovely little book about the things that happen in boys heads. Henkes has a deep and humorous feel for the thickets of thought, and a very fine way with word and mood. An excellent book.

Two books this year, however, of the few I have read, I have really liked. One is Bird Lake Moon by Kevin Henkes (Greenwillow, 2008), a lovely little book about the things that happen in boys heads. Henkes has a deep and humorous feel for the thickets of thought, and a very fine way with word and mood. An excellent book.

The other book I quite liked is Eleven by Patricia Reilly Giff (Wendy Lamb/Random House, 2008). She has written many, many great books over the years, and you almost expect someone with a track record like that to lay back and do some automatic writing.

No. Eleven is a story of a boy who is struggling with the knowledge of who he is, why he lives with who he does, how he connects with people, and his place in this world. It is as fresh and lively as a debut novel by a very good writer.

Giff is someone I’d love to emulate: a long career on an upward incline. Great little book. Now, I think I’ve said little book twice, which is, I guess, the sort of story that appeals to me. No dragons, no explosions, just people.

What do you do outside of the world of youth literature?

Is there anything outside? Actually, I write so very much (and more and more slowly) that there is little time for anything else. But I love yard work, especially mowing the lawn, which to me has a postwar, suburban, life-is-all-open-before-us sort of feel about it.

I recognize that sometime in the future we will have no lawns, no private houses, no fuel, no children, no books, no life, so I treasure the one hour a week I spend making my little plot look good.

The other thing is that I play electric guitar. Not loud, because I live in a neighborhood, but yes, blues, wah-wah pedal, distortion, and all that. My faves: Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, and Jeff Beck. Also . . . Jeff Beck.

What can your readers expect from you next?

First of all, I have this new series coming from Scholastic, starting in January 2009, called The Haunting of Derek Stone. It is a dark comedy, with the emphasis on dark. It’s a ghost story, with a kind of twist, an exercise in Southern Gothic fiction, a genre I love, and a Louisiana thriller.

First of all, I have this new series coming from Scholastic, starting in January 2009, called The Haunting of Derek Stone. It is a dark comedy, with the emphasis on dark. It’s a ghost story, with a kind of twist, an exercise in Southern Gothic fiction, a genre I love, and a Louisiana thriller.

It is more novelistic than my other series work and for older readers, who can handle the truth…and the fear. If it’s deeply frightening, it’s meant to be.

Derek is a boy in trouble, and I hope we all never get into that kind of trouble, but we may want to hear his story.

The first one, called City of the Dead (a reference to the above-ground cemeteries in New Orleans), comes out in January.

About the novels, when I wrote Firegirl I made the silent decision that my novel-writing would be as different as can be from my series writing. If the Droon stories, for instance, are continuations of the same story, my novels would be vastly different from one another.

This may wreak havoc with an editor or a publisher (not Little, Brown, I must say, who are adventurous and fun), but a writer does want to be able to stretch. So, while Firegirl was a quiet school story, and The Postcard a magical realist noir crime comedy mystery, my next book will be different again. In tone, it may relate more to Firegirl, but it will be quite different. A piece of historical fiction. Perhaps even experimental in the way that it tells a story. Short. Hard. Unforgettable, if I have my way. Something you will love dearly or hate intensely.

I mean, I have, what five, eight more novels to go before they run me out of town, so I want to write what I want to write. This is a story that needs to be told. Something that happened to me in the dark days of the previous century. Is that vague enough?